Table of Contents

Music and Visual Art

Composers have often found inspiration in similar aesthetic aims as visual artists, and it is this relationship between the visual and the aural that this topic will explore. From music that illustrates art to music whose notation is a work of art, from artists inspired to create in both visual and aural mediums to visual and aural artists who chose the same titles; the following are examples of the many kinds of parallels between visual art and music that have occurred over the centuries.

Mussorgsky: Aural Representations of Art

In 1873 Russian architect and painter Viktor Hartmann died suddenly of a heart attack at the young age of 39. He had been a well-loved figure in Russian cultural life, and his work was part of a new movement to support modern Russian artistic perspectives. After his death, a retrospective exhibition of his works was put on, and composer Modest Mussorgsky was one of the many who came to view it. As part of a group of composers known as the Mighty Five, Mussorgsky was also interested in portraying Russian themes in his music, and Hartmann's works were an inspiration.

Mussorgsky wrote a piano piece based on the occasion, Pictures at an Exhibition, with each of the ten movements depicting one of Hartmann's paintings and drawings. These movements are separated by sections of music titled "Promenade" that give the listener the impression of strolling through the gallery to view the next painting. The piece was later orchestrated by other composers, and is generally known in its most famous orchestration, that of French composer Maurice Ravel.

A "Promenade" opens the work, with the melody in the trumpet. The melody is in an irregular meter of alternating five and six beat measures. It is also built on a pentatonic scale of five notes. Both of these elements are characteristics of folk music, and were often used by classical composers to evoke folk traditions or nationalist traits. In this case, they are evidence of Mussorgsky's interest in portraying Russian themes. Additionally, by composing the "Promenade" sections of the piece Mussorgsky has added the element of motion through time to Hartmann's art. Listen to the first "Promenade" below:

Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition: Promenade

The final movement of the work depicts Hartmann's design for a commemorative gate to the city of Kiev, then in Russia. The gate was intended to celebrate the tsar's survival of an assassination attempt, but the project lapsed during the planning stages. Mussorgsky's musical depiction of Hartmann's design nevertheless draws the gate into Russian culture. Just like the three arches in the drawing, the movement has three main themes, arranged in an ABABCA pattern. The first theme, played by the brass, illustrates the grand scale of the gate. This alternates with a hymn played by the woodwinds, thus illustrating the prayer room above the middle arch. The particular tune Mussorgsky used comes from a Russian Orthodox chant, serving to reference the early birth of Christianity in Kiev. And finally, the third theme (C) is the return of the promenade theme. This places the listener not only inside the gallery exhibition, but also inside the picture itself. Musorgsky's use of bells near the end of the movement references the bell tower in the picture and gives the final movement a sense of majesty.

Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition: X. The Great Gate of Kiev

Debussy and Impressionism

Frequently, the kinds of ideas that motivate artists in one field spill over to other fields and are interpreted through other mediums. This creates parallels between different genres of art even when there are no direct connections between the creators of these different genres. This is the case in the next example, in which we can draw parallels between the style of Monet's Impressionist paintings and Debussy's music, even though the two artists never collaborated.

Impressionism is an artistic movement that began in Paris in the 1870s when a group of painters decided to put on an exhibition of their works outside of the approved national salon structure. They were rebelling against both this highly exclusive system of exhibiting, and also against the mainstream style of painting that it supported. Instead of highly detailed, realistic portrayals of the world, these painters sought to capture the sensation of a moment. In pursuit of the naturalness of the play of light on a surface, painters focused on the effects of color and used loosened brush strokes. Their work aimed for a sense of spontaneity and prized suggestion over exacting details. A critic writing about this first exhibit wrote that the painters had sloppy technique, and consequently could only capture the "impression" of things rather than managing to paint actual things with any success. From this negative review the name impressionism was born to describe the style. One of the most well known works in the exhibit was Monet's Impression: Sunrise, which also contributed to giving the style a name.

Impressionist music can be described in similar ways to the paintings: it emphasizes the effects of color (or timbre) and seeks to capture the sensation of a moment. But Impressionism in music was reacting to very different trends than the painters were. Impressionist composers wanted to move away from the grandiose and the overly emotive, traits that they saw as a sign of fin de siècle decadence. To achieve this, they not only focused on color rather than melody, but also used dissonances that simply failed to resolve in any expected manner. This creates a stasis in the harmony, which causes the music to sound very atmospheric, as it loses any sense of progressing forward.

For an example of the style we will turn to Debussy, although he would have identified himself as a Symbolist, another important literary and artistic movement of the late nineteenth century. Now that the term Impressionism is used without intending insult, Debussy is often considered a proponent of the style. His set of orchestral pieces, Nocturnes, shows many of the Impressionist techniques in music, so we will look at the first one, Nuages (Clouds).

The first thing to notice is how the different instruments are used to build a palette of color, much the way a painter would build from a palette of paint colors. Instead of presenting us with a clear melody-and-accompaniment texture, Debussy gives each instrument one kind of lyrical line to play. Each time we hear that instrument it plays the same line in the same range, or with only minor alterations. In this way our attention is drawn to the quality of sound rather than the manipulation of motivic or melodic material, as a composer in the Beethoven tradition would have done.

The second important element of this style is the lack of cadences in the piece. The only cadence appears quite near the beginning, in order to establish the tonic for the listener and give us a sense of "home." But even this cadence is weak, and throughout the piece the tonic note, B, remains important because it is continually asserted as a pedal beneath the other instruments or isolated in range or repetition to bring it to our attention. And even though the piece ends on B, we are not given the finality of a cadence there either. The other notes simply fall away until only B is left. This lack of cadential motion throughout the piece is what gives it that static, atmospheric mood, and we are only sure of where the tonic is because of the way it is continually asserted.

Another technique Debussy uses to create a sense of stasis is the choice of scales that lack semi-tones. Semi-tones create movement, or resolution, toward their closest neighbor, and were used to increase the emotive power and longing that characterized Romantic music. Part of rejecting that earlier style and avoiding cadences was avoiding semi-tones. So Nuages is built on the whole-tone scale and a pentatonic scale, both of which lack semi-tones. Moving from one set of scalar material to the other helps to create the ABA form in the piece, with the middle section using the pentatonic scale.

Listen to the movement below, noticing the prominent use of instrumental color and the atmosphere that the lack of harmonic progression creates. Like the Impressionist artists, Debussy's goal was to create music with a suggestive quality, music that focused on the sense experience of a moment. His descriptive titles help to communicate what his music is illustrating.

Debussy, Nuages

Schoenberg and Expressionism

In the decades around the turn of the twentieth century, an artistic movement called Expressionism began to take hold. One of the earliest creators of the style was Edvard Munch in Norway, but the movement was especially strong in Vienna. Expressionism was a reaction to the naturalistic and objective perspective of Impressionism, and it was a continuation of Romanticism's expression of subjective inner emotion. Society continued to modernize and the advances of industry caused increasing numbers of people to live in urban environments. The artists, writers, and musicians that would become known as expressionists tried to address the inner anxiety and turmoil they felt in this environment. Expressionist artists focused on the darker human emotions, often verging toward violence, in an effort to portray what they saw as a suppressed subconscious. Sigmund Freud was also working in Vienna at this time, and his ideas influenced many artists as well as psychoanalysts.

Arnold Schoenberg participated in this movement as both an artist and a composer. He created a series of paintings that focus on the face, but with all features blurry except the eyes. These eyes stare out at the observer with an eerie intensity, communicating not only the artist's loneliness but also that of the observer. These works cause the watcher to feel that they are also being watched.

At about the same time, Schoenberg began experimenting with his atonal style, freeing himself from the restrictions of tonality. He called it the emancipation of dissonance, as dissonances in his music no longer required resolution to consonance. He took the familiar tools of Romantic expression, the means to communicate intense emotion and longing, and saturated his music with them. As dissonance no longer required resolution, so keys soon lost their definition, and the distinction between major and minor became blurred. Chromatic leading tones and dissonant intervals pile up on top of each other, requiring neither resolution nor clarity. Schoenberg himself admitted that these works, once completed, were beyond his own ability to analyze, thus making them truly an expression of the unconscious or irrational.

Schoenberg's Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16 (1909) provides an example of his style at this time. In place of key relationships and harmonic progression, small motivic units gain importance. These little melodic cells are layered and juxtaposed to create formal structure, and often result in jarring dissonances. In addition, Schoenberg was experimenting with a new idea that he called Klangfarbenmelodie, or tone color melodies. This refers to the practice of overlapping different instruments within a melody, so that the timbre of the melody gradually shifts into a different color. This technique is especially evident in the slow-moving third movement of the work, "Chord-Colors." The fourth movement, "Peripeteia," offers more rhythmic and dynamic interest, as well as rich motivic saturation. Listen below and see if you think these techniques help the Expressionist goal of giving voice to a unique inner subjectivity.

Schoenberg, Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16, No. 3 "Chord-Colours"

Schoenberg, Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16, No. 4 "Peripeteia"

Hildegard von Bingen: Composer and Artist

Occasionally an artist's inspiration blossoms in more than one type of art, as we saw with Schoenberg. This was also the case for the twelfth-century abbess Hildegard von Bingen. She had powerful visions throughout her life that she documented through illustrations, poetry, and musical settings of that poetry. Her position in a convent gave her access to an intellectual life that few women in her day were allowed. Likewise, as her visions were thought to come directly from God, they had an authority that her own voice could not have. She became well known throughout the German lands and neighboring countries, and was so respected that even kings and the pope sought her advice and prophesies. In addition to her creative endeavors, she founded two convents and wrote books on topics ranging from biology and astronomy to politics.

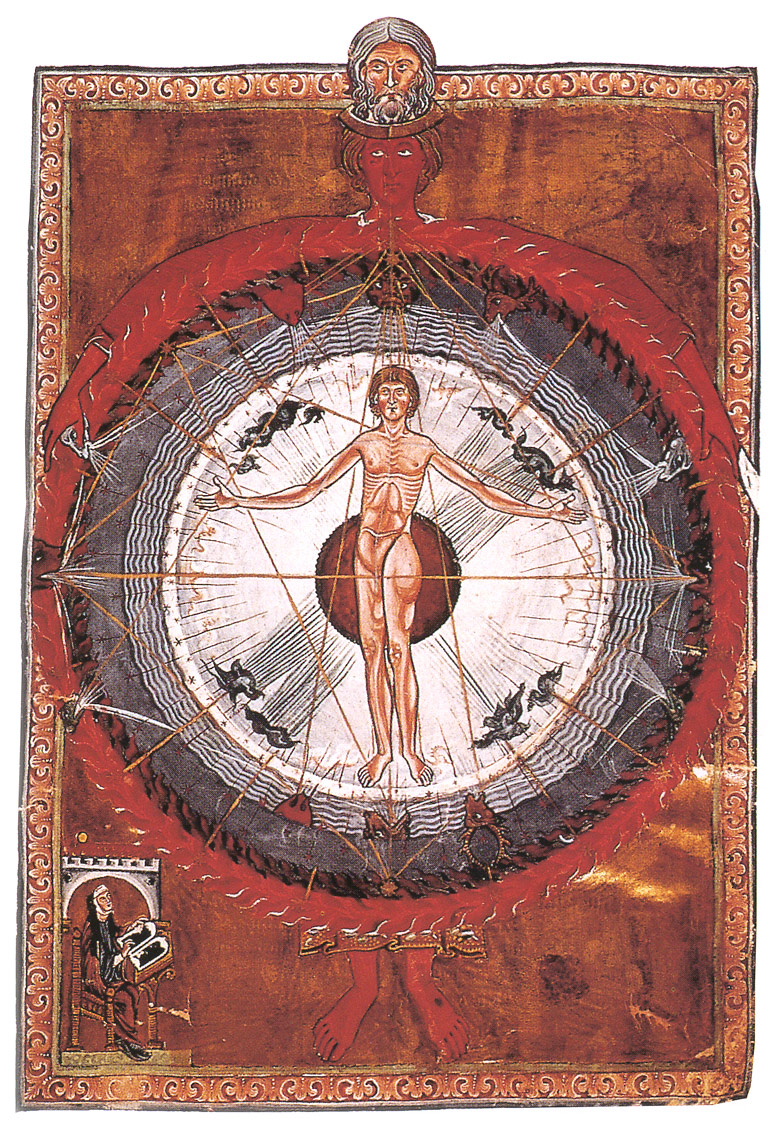

Ave generosa is an example of the kind of piece Hildegard would have written for her fellow nuns to sing. It is a hymn to the Virgin Mary, a subject that occurs frequently in her work and must have resonated for her, being a woman of some influence in a society where women had few rights. Hildegard seemed especially interested in the relationship between her words and music, and used her compositions as a means of further contemplating issues that appeared to her in visions. Ave generosa is monophonic, like most church music of the time, but with the striking leaps and large range that were typical of Hildegard's compositions. The illustrations below are among those that decorated Hildegard's writings and music, also inspired by her visions.

Hildegard von Bingen, Ave generosa

| Original Latin | English Translation |

| Ave, generosa, Gloriosa Et intacta puella; Tu, pupilla castitatis, Tu, materia sanctitatis, Que Deo placuit. |

Hail, girl of a noble house, Shimmering And unpolluted, You, pupil in the eye of chastity, You, essence of sanctity, Who were pleasing to God. |

| Nam hec superna infusio In te fuit, Quod supernum verbum In te carnem induit, |

For the Heavenly potion Was poured into you, In that the Heavenly word Received a raiment of flesh in you, |

| Tu, candidum lilium, Quod Deus ante omnem creaturam Inspexit. |

You, the lily that dazzles, Whom God knew before all his other creatures. |

| O pulcherrima Et dulcissima; Quam valde Deus in te delectabatur. Cum amplexione caloris sui In te posuit ita quod filius eius De te lactatus est. |

O most beautiful And delectable one; How greatly God delighted in you. In the clasp of His fire He implanted in you so that His Son Might be suckled by you. |

| Venter enim tuus Gaudium habuit, Cum omnis celestis symphonia De te sonuit, Quia, virgo, filium Dei portasti, Ubi castitas tua in Deo claruit. |

Thus your womb Held joy, When all the Heavenly harmony Chimed out for you, Because, o virgin, you bore the Son of God Whence your chastity blazed in God. |

| Viscera tua gaudium habuerunt, Sicut gramen super quod ros cadit Cum ei viriditatem infudit; Ut et in te factum est, O mater omnis gaudii. |

Your womb knew delight Like the grassland touched by dew And drenched in its freshness; So it was done in you, O mother of all joy. |

| Nunc omnis Ecclesia In gaudio rutilet Ac in symphonia sonnet Propter dulcissimam virginem Et laudibilem Mariam Dei genitricem. Amen. |

Now let all Ecclesia glimmer With the dawn of joy And let it resound in music For the sweetest virgin, Mary compelling all praise, Mother of God. Amen. |

Album Art

For many popular musicians, their look is as important as their sound. Parallels can be made between these musicians and composers such as Schoenberg and Hildegard in the way that their creativity operates in multiple mediums. In the case of Radiohead, their album art seems to be making as much of a statement as their music. The style of each album's artwork was purposefully designed with the sound of the album in mind. For the album In Rainbows, a special release of the album included a hardcover book of album art and additional art by Stanley Donwood, as well as extra studio takes and LPs. Each of Radiohead's albums is illustrated with artwork that follows a particular visual inspiration. For instance, The King of Limbs draws on folklore and fairy tales and their ubiquitous forest settings for its visuals.

Even the music videos can carry on this visual element, as with the video for "House of Cards" from In Rainbows, which uses 3D mapping technology instead of lights to record the video. This mapping is then portrayed in many colors, thus referencing the album's title. For a band whose lyrics so often pointedly speak out about something, it is hard to imagine that the visual elements of their albums have any less importance, artistically speaking. Take a look at the album art below and the video for "House of Cards," noticing how integrated the band's image is through these various mediums.

Radiohead, "House of Cards" from In Rainbows

Whistler and Chopin: What's in a name?

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Chopin was one of the first specialist composers, choosing to compose the majority of his pieces for solo piano. His works had a certain intimate quality, both because of using a single instrument, and also because of the way Chopin wrote for that instrument. He was well known for the genres of the polonaise and mazurka, both with a Polish flavor that referenced his homeland, as well as etudes and preludes. But another significant genre for Chopin was the nocturne, or night song. This was a genre originally played on the guitar, usually as an evening serenade from a gentleman suitor standing at the window of a lady. John Field in Ireland composed some early examples for the piano, but Chopin gave the genre its notoriety.

Chopin’s nocturnes evoke the mood of the night, with their elegance and subdued dynamics. Traces of the genre’s roots are evident in left-hand arpeggios that mimic guitar strumming. Melodies are usually quite lyrical, as if being sung, and the nocturnes are overall delicate and graceful in tone. They typically contain a contrasting middle section, lending the pieces a ternary form, with the final section repeating earlier material but with added ornamentation and embellishment.

With this definition of the genre in mind, what can James McNeill Whistler have intended by choosing to title a handful of works with the musical genre, nearly a quarter century after Chopin’s death? These paintings have nothing to do with Chopin, or even French subjects, and certainly little to do with musical subject matter. But it had become very popular for artists to describe their work and their artistic goals in musical terms. Painters frequently spoke of a "harmony of color" or "harmony of line" that they were striving for. Thus, musical metaphor was a familiar technique for artists. Scholars have suggested that Whistler liked to draw parallels between his artistic style and the lack of narrative in many genres of instrumental music. His titles included other musical terms as well, such as "symphony," "arrangement," and "harmony."

Despite the absence of any clear explanation for Whistler’s titles, it is possible to find parallels between his nocturnes and those of Chopin. There is the obvious choice of nocturnal settings, of course. But both artists seem to have converged on a particular mood of the night. Rather than the fearful and aggressive aspects of nighttime adventures, both portrayed instead the placid and serene moments of quiet that occur when the world’s business has been put to bed. Compare Whistler’s nocturnes to a few of Chopin’s and decide for yourself why the painter may have chosen such titles.

Chopin, Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, Op. 15, No. 2

Chopin, Nocturne No. 19 in E minor, Op. 72, No. 1

Graphic Notation: The Score as Art

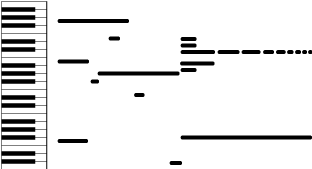

Early twentieth-century piano rolls also bear some similarities to graphic notation, as they operate on a time-pitch scale of the type that many composers found useful in graphic notation.

In recent decades, as composers have experimented with the incorporation of electronic elements and other new ways to make sound, traditional ways of notating music has become quite limiting to them. Notation is, after all, merely a symbol for sound, directions to the performer that tell what to play, when, and how. If these directions become inadequate for symbolizing sound, it only makes sense that composers would come up with new systems to communicate with their performers. Graphic notation often specifies one element of the sound, such as pitch or duration, leaving other elements up to the performer. Thus, graphic notation overlaps with our discussion of the freedom of the performer in the context of improvisation.

Graphic notation ranges from the highly detailed, as with many of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s scores, to the utterly simple, as with some of Morton Feldman’s. Other composers create scores that look more like art than notation. Browse this gallery of graphic scores from The Guardian for a variety of examples:

"Graphic music scores - in pictures," The Guardian, October 4, 2013

Graphic notation offers experimental performers a new language to communicate their intentions. But composers have also used traditional notation arranged in a graphic way to tell the performer something else about the piece, perhaps its mood or purpose. This is the case with some of George Crumb’s works, but also many medieval manuscripts. In these, the staff may be arranged in a circle or a heart, or some other descriptive visual shape.

In all of these cases though, the listener may be completely unaware of the shape the score takes. Which is to say that innovative forms of notation are not part of the listener’s experience of the musical sound. Rather, such notation only has an impact on the performer. Composers have to be aware that their choice of notational language may ultimately have an impact on how the music is performed, but the listener will be none the wiser.